Athabasca mud

Clay has tied people, traditions and the land together in Athabasca for generations

Allendria Brunjes, Athabasca Advocate

For those who know where to look, there is nothing secret about Athabasca clay.

But those who start searching may find themselves lost in a long history that is recorded in many different ways.

Its past is written in the red bricks of local buildings.

It’s woven into the vases and bowls thrown, glazed and fired by mid-20th century artists who lived and worked in town.

The methods to work it are passed on with an oral tradition via groups like the Athabasca Pottery Club.

Everywhere you look, you’re likely to see Athabasca clay. You just don’t know you’re seeing it.

Early days

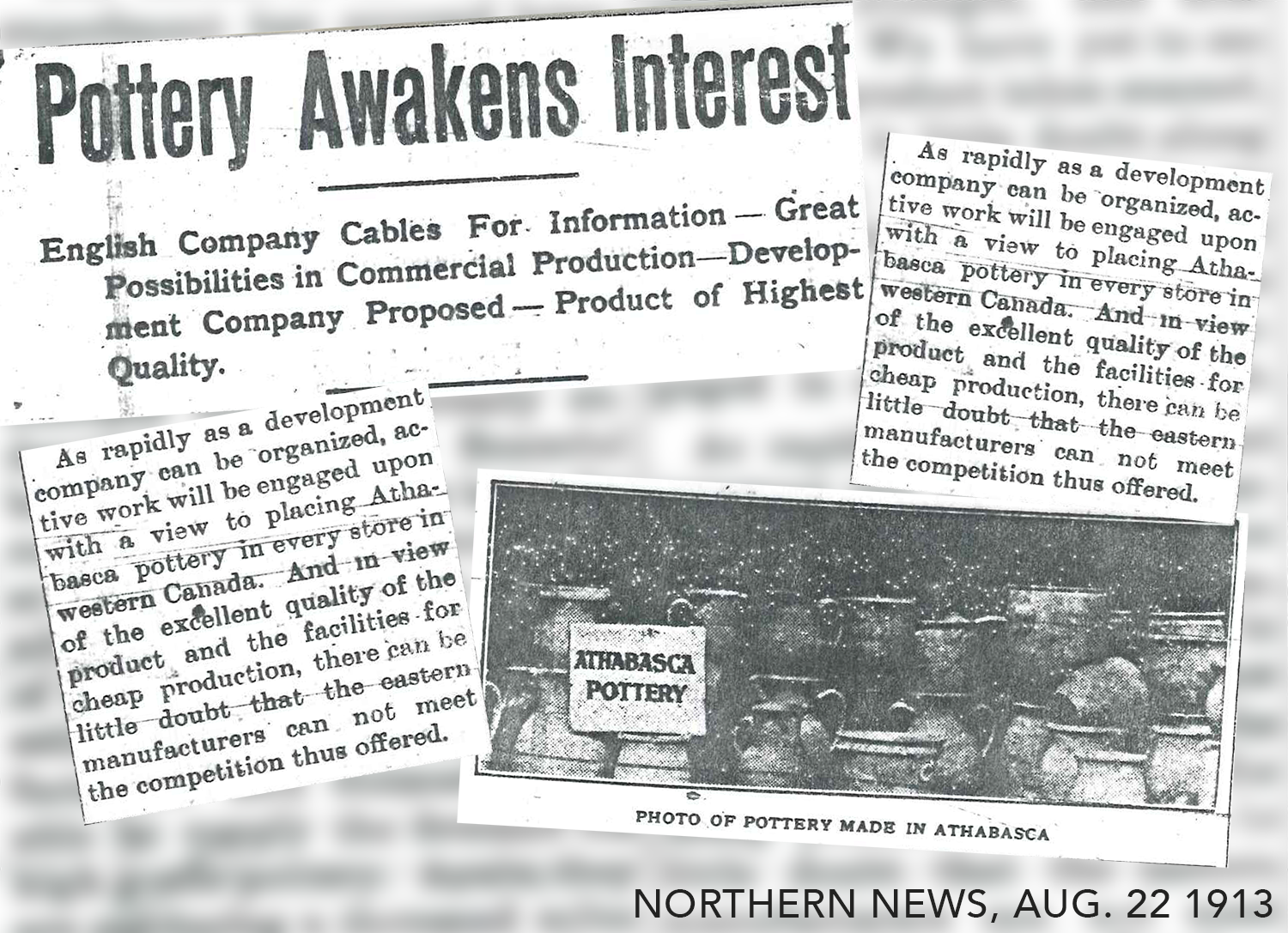

The first evidence in the Athabasca Archives of the commercialization of Athabasca clay is in the form of a short article from 1912. Published in the Northern News on Sept. 21, 1912, it notes that the machinery for a brick-making plant – with the capacity to make 50,000 bricks daily – had arrived for Claude Thillet.

“Experiments with the clay on the Thillet property have proved a complete success, and the new plant will be placed in order to supply the trade in the spring,” the article proclaims.

Carrie-Ann Lunde, writing for the Royal Alberta Museum, stated in a history piece that Thillet had found clay on his farm south of the town. His bricks were used to rebuild many local buildings after the 1913 fires decimated the town. One was the Hudson’s Bay Company store, which closed in 1924 and was demolished in 1966.

The Athabasca Times reported in 1913 that his company also made pottery, hiring German potter Edwald Walden to be in charge of the work.

Despite a promising start, ceramics were not destined to be a mainstay in Athabasca’s economy. Lunde wrote that Thillet died in 1920, and David Keir purchased his homestead. The story of Thillet’s clay and brickyard ends there, but that of Athabasca mud goes on, though there is a break.

Rebirth

Alberta’s I-XL Masonry Supplies began mining clay from Athabasca in the 1960s, and continued to do so for decades.

The company was not the only party interested in Athabasca’s dirt.

Local television pioneer and former mayor Ed Polanski put his hands in the mud in 1964, starting up short-lived Athabasca Clay Products.

"Typical, gambling, reckless entrepreneur that I am, I ended up with a pottery I never intended," Ed Polanski recalled in Marylu Antonelli and Jack Forbes’ book, Pottery in Alberta: The Long Tradition.

Royal Ontario Museum programs manager Conrad Biernacki published a historical article about the company and its products in 2009. He wrote that it has been estimated that the company produced about 150,000 pieces, noting that local collectors and residents in town have a strong attachment to them.

Biernacki wrote that in the beginning, the wares were turned on a wheel by Swiss potter Alfred Messerli. Antonelli and Forbes wrote that Polanski said his biggest difficulty was finding craftsmen.

“Our schools don’t turn out craftsmen,” he said. “We don’t recognize pottery as a legitimate trade. I had to import my craftsmen and that was a very expensive business.”

Biernacki also said while Messerli threw the pottery on the wheel in the early days, Eialin Armfelt was the first decorator, etching designs like maple leaves, bulrushes, whooping cranes and mountain and prairie scenes.

Messerli left Athabasca in 1966, and Armfelt left the pottery in 1967.

Antonelli and Forbes also write that Polanski said there was a market for his product, and “he could not produce enough to satisfy it.”

Phyllis Polanski, Ed’s wife, told Biernacki that the main challenge was transportation costs, moving finished product to markets.

They also noted that the company never made a profit, and the company closed its doors in 1968.

In 2009, after months of research and preparations, Biernacki held Athabasca Pottery Discovery Day in town, celebrating Athabasca Clay Products Ltd. Messerli came back to town, joined by about 130 people from all over Alberta who were keen to know those “carrying on the legacy of Athabasca pottery,” the Advocate reported.

Polanski passed away in October last year. His influence lives on in many ways. Athabasca Clay Products is just one avenue – but that’s another story.

Athabasca Pottery Club

As Athabasca Clay Products lived its brief existence, a small dedicated group of people started the local, not-for-profit Athabasca Ceramics Club, now known as the Athabasca Pottery Club.

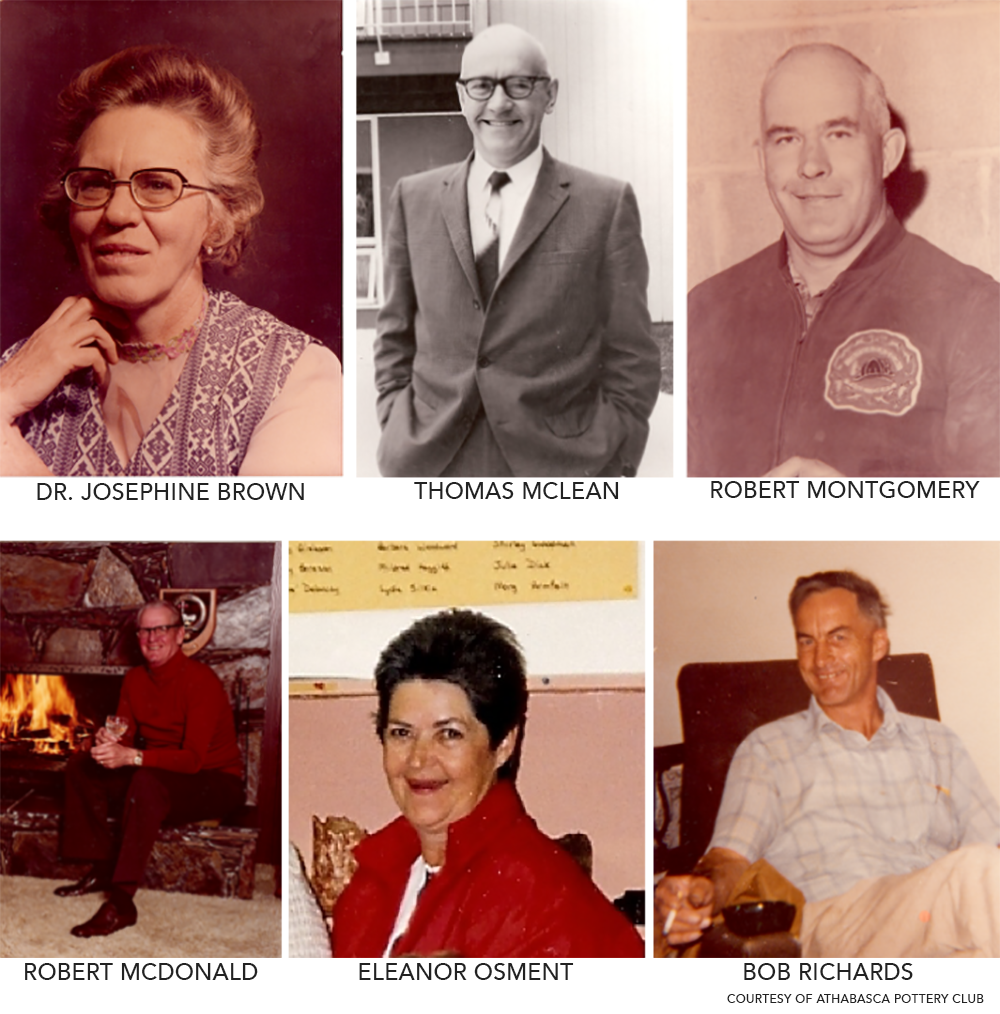

Dr. Josephine Brown, Thomas McLean, Robert Montgomery, Robert McDonald, Eleanor Osment and Bob Richards were the six founding members on Nov. 6, 1961.

Using donated clay from the Loxam farm, located just south of town, the group aimed to “To carry on any benevolent, philanthropic, charitable, scientific, artistic, social, educational, and other similar activities in connection with making pottery in the Athabasca District,” according to its mission statement.

Over the years, the club has evolved, purchasing new kilns and refining the process of clay production to an art.

Monica Wolanuk, who was the club’s president a few years ago, is now the club’s in-house historian.

She said her goal is to compile as much as she can about the club’s history, bringing the old media forms together with new ones.

“I basically worked at trying to combine the really old with the new, and using of course the technology that we have today that we didn’t back then,” she said. “So that we can hopefully keep that information around forever.”

A lot of that history is kept going through people and practice.

“The information we learn was all by word-of-mouth,” Wolanuk said, while speaking about Eleanor Osmont, who taught club members about underglazing. “Pretty much everything that’s been done here for 55-plus years has been through passing down from one person to another.”

Wolanuk said the club, which has about 30 regular members and 16 current students, just finished a session of classes that ran from October through December. There are also classes for children that run as part of the town’s recreation program in the summer.

“We’ve always kept the costs really low, so we’re making it accessible to people to be able to try it out and enjoy it,” she said.

The club’s current president Heather Betts said a 10-class session costs $60, which includes the clay, firing and instruction. A year-long membership costs $120.

“I didn’t even know this club existed three years ago,” Betts said. “And then a friend of mine said, ‘I started in this really great club – you want to come try it?’ Here I am, three years later.”

One Thursday afternoon, a few women gathered around the lunchroom table – some to talk to the lady from the newspaper about the club’s history, others to listen and absorb as much as possible.

Rosie Guay was one of the speakers.

Betty Salé was another one of the speakers.

Betts listened, as did Jackie Jorgensen.

Having been a member of the club for 44 years, Guay holds a lot of the club’s history in her mind.

Betts pointed out that Guay did all the firing for a number of years. She has now passed the knowledge on to four or five other people.

Guay said she was invited to the club by a couple of instrumental members – Irene Schinkinger and Osment.

She said they started in “a dungeon,” in a basement room that was where the Nancy Appleby Theatre basement is today.

“When you think of all this that we have now, it blows my mind, really,” Guay said. “To think of how far advanced we are.”

Meetings like this little one around cups of coffee and biscuits are a reminder of where the club has been, letting that lead where the club goes in the present.

“The Athabasca Pottery Club has a very rich history affiliated with the town and Alberta,” Wolanuk said. “Pottery, too, it’s all about using your hands. It’s never been about having a history – electronic history.”

She added that for most clubs and guilds, the historical element has only really become important in the last five years.

“And that’s good, in a way, because at least our history will stay,” she said. “Hopefully, the club keeps going, but at least years from now, they’re going to be able to appreciate what was started here and what’s still going strong.”

As that history accumulates in places that are easily accessible, she added the age of the internet means the club is “probably not going to be much of a secret, anyway.”

“That’s OK,” she said. “As long as we still function the way that we always have, then it’s OK. We don’t mind letting our best-kept secret get out there for everybody else.”

Getting dirty with Athabasca mud

The Athabasca Pottery Club took Advocate publisher Allendria Brunjes through the first part of the club’s process of producing a work, from pugging to wedging to throwing. It is a long-standing practice that has been tried and tested for years, tailored specifically to the local clay.

Lunde wrote that Athabasca’s club is the only one in Alberta to still make its own clay.

She said Athabasca clay is unique to the area and differs from the majority of clay in Alberta. It is a versatile clay, she wrote, because it does not expand when it gets wet and maintains its shape.

Wolanuk said it is a low-fire clay, earthenware. It turns red after firing.

The first step in the process is actually getting the clay. Club members head down to the Loxam farm – which still donates clay to the club after 55 years – and collect dirt off the banks of the Tawatinaw River, shoveling it into their space in the basement of the Old Brick School through a window.

The club leaves portions of the dirt in water. It is later sifted and left to dry out on sheets.

After the clay has hardened a little, it is rolled up and thrown into the “pug mill,” which works the clay into a round which is then wrapped in plastic and stored in an old refrigerator.

When someone’s ready to use it, the clay is then “wedged,” a process involving pushing and rolling the clay that until It looks like a ram’s head, making it easier to work with and less likely to blow up in the kiln. Smooth it out when it’s done.

When it is handled, the grey muck is solid. Smooth. Fine. It feels like a very nice clay.

Taking the wedged piece, Jorgensen shows me how to centre the clay on the wheel. Hers looks great – mine falls off.

She shows me how to pull the clay and work it on the wheel until it’s ready to make a bowl. Which she does, with ease and skill.

She takes my piece of clay, and centres it on her wheel, sitting me down to show me, hands on, how to pull the clay up and make it workable.

The lump of clay turns into a lump with a hole in the centre. The hole gets bigger, as the wheel spins the clay around my fingers. I make a few critical errors, which Jorgensen fixes.

(Photo by Heather Betts)

(Photo by Heather Betts)

With guidance, we get to a place where I have the beginnings of a bowl.

Next month, I have to go back and work the clay some more. Then there is the glazing and the firing process.

It certainly has given me a new appreciation for dinnerware.